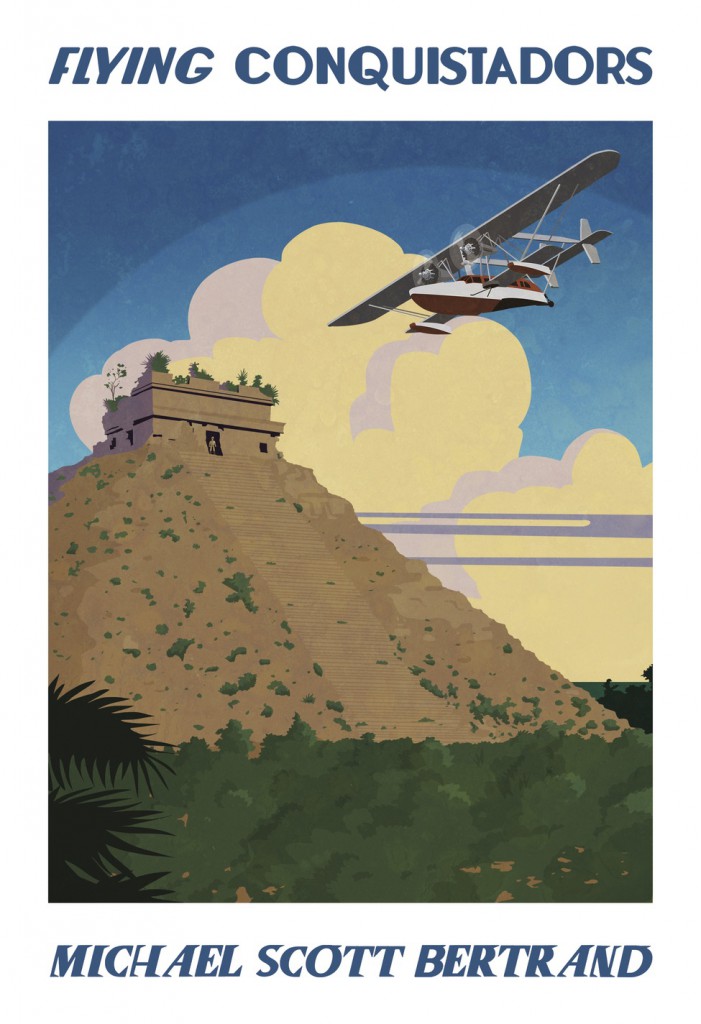

Was legendary Mayan archaeologist (and Flying Conquistadors character) Sylvanus Morley the real-life Indiana Jones?

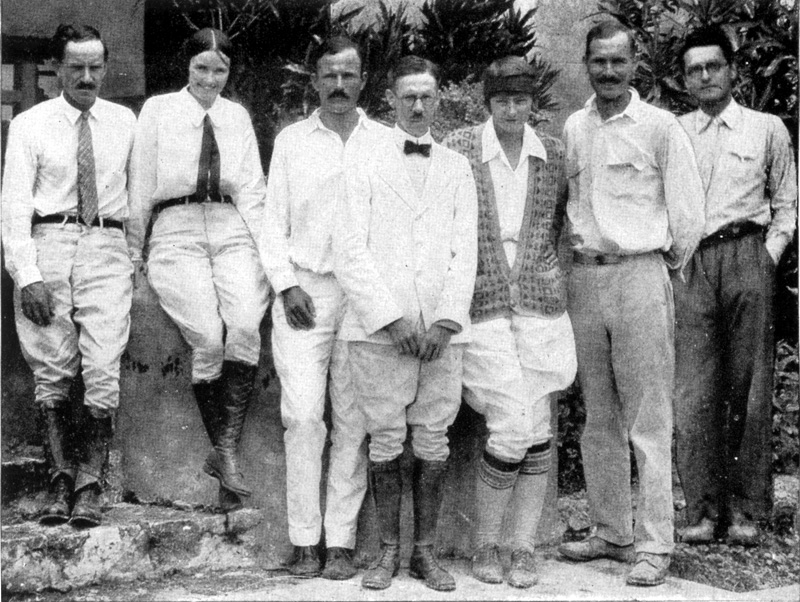

If you Google Morley’s name, you’ll find multiple references suggesting he was an inspiration – perhaps one of many – for everyone’s favorite idol-seeking adventurer. You’ll also come across this picture of a young Doctor Morley in the field, with his glasses and scruff, looking remarkably like a cleaned-up Doctor Jones from the college scenes in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

That’s not the only similarity. During World War One, Morley used his archaeological credentials for cover as he spied for the United States. Known as “Agent 53,” he covered over 2,000 miles scouting for rumored German submarine bases throughout Mexico and Central America and kept tabs on pro-German sentiments in the region. He filed over 10,000 pages of reports. His Wikipedia page includes a quote stating he was “arguably the best secret agent the United States produced during World War One.” (His dual-natured activities, which only came to light after Morley’s death, drew criticism from some in the archaeological community, a topic covered on Morley’s Wiki page. For deeper reading, see The Archaeologist was a Spy by Charlie Harris.)

And some of Morley’s adventures would seem to right out of a screenplay:

In 1916 Vay almost lost his life when his party, returning from his great discovery of Uaxactun with its earliest known dates, was mistaken for a party of revolutionaries and ambushed by a detachment of Guatemalan troops. The doctor and the guide, who were at the head of the party, were killed. Morley owed his life to the fact that a few minutes before a liana had caught and ripped off his glasses; by dismounting to pick them up he lost his position at the head of the column, and was still in the rear when the action began. Many a time Morley has described those events to me: the sudden volley of rifles, the helter-skelter diving into the sea of forest on each side of the narrow trail, and the hours that he lay hidden in a clump of thick vegetation, afraid that a movement would bring a fresh volley of shots. That must have been the only time that Vay ever felt the forest was friendly. Then the night journey to safety on the British Honduras side of the boundary had to be undertaken. On another occasion, when relations between U.S.A. and Mexico were at their worst, an inebriated Mexican general, with a revolver in each hand, was dissuaded with difficulty from shooting Morley and his party who had taken insecure refuge under tables and behind lampposts. (taken from a remarkable obituary on Morley)

So it’s tempting, at least on first glance, to say Doctor Morley might be Doctor Jones. But if you dig deeper, you’ll find the real-life temple-finding archaeologist had little else in common with his rumored Hollywood counterpart. Sylvanus Morley hated the jungle, hated the heat and humidity, and despised the bugs. Over the decades he had numerous bouts with malaria and other jungle ailments. He was a small man, shorter and less athletic than most of his counterparts, and not the type that made a habit of swinging from vines or outrunning boulders. He didn’t wear a leather jacket and a fedora, preferring suits and ties (despite the heat) and tall boots that only accentuated his slight size. To protect himself from the relentless heat, he almost always wore a pith helmet or a sombrero.

Note: We have reached out to the Spielberg and Lucas camps for comment. While we await an answer, here’s a list of possible Indy inspirations that places Morley at #3.

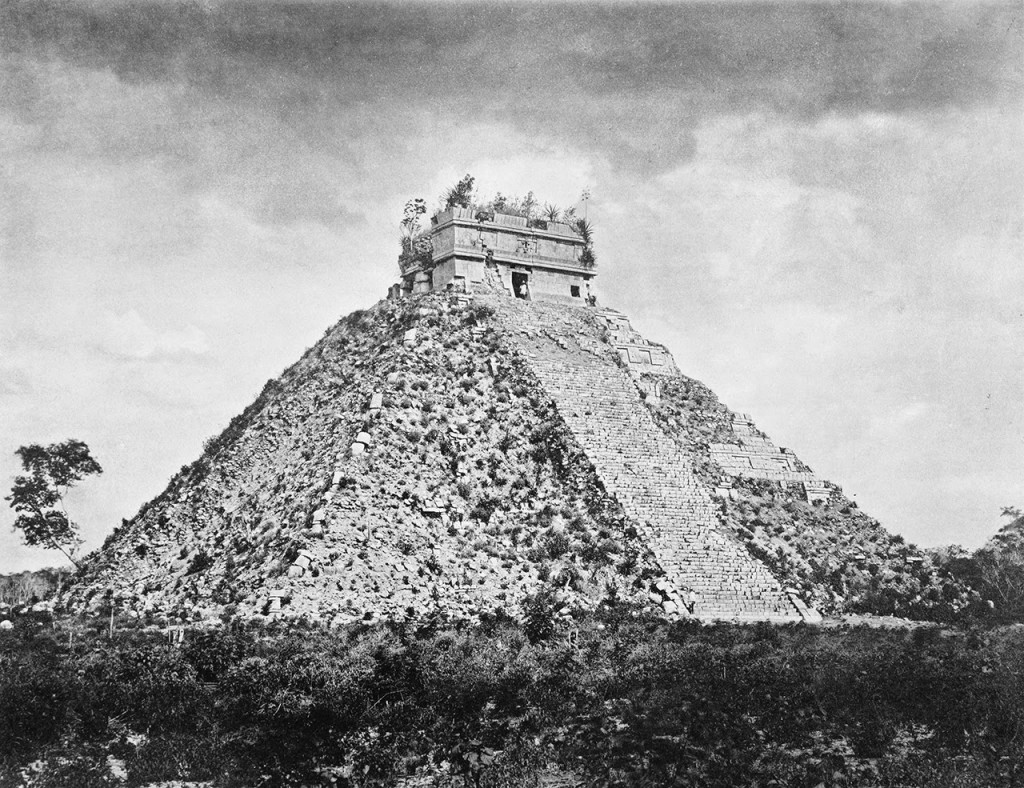

There is, of course, no debate about Morley’s place in the history of American archaeology. His contributions to our understanding of the Mayan culture and their language continue to influence archaeologists today. But his legacy is most noticeable in the magnificent Mayan sites he helped uncover and restore. It was Morley who persuaded the Carnegie Institution to engage in large-scale work on Mayan sites, at a time when much of the archaeological community was focused on Egypt (this was before Tut’s tomb was discovered) and the Old World.

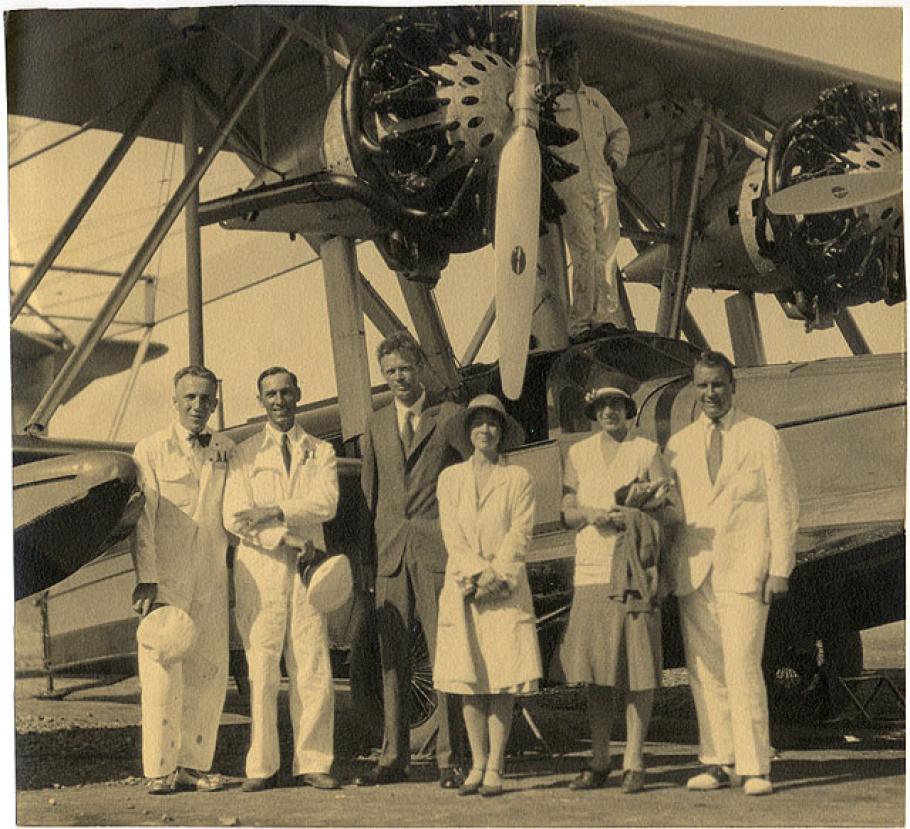

Morley’s involvement with Chichen Itza is a story unto itself. Early in his career (1912), he made a bold proposal to the Carnegie Institution to excavate and restore much of the ancient city. Morley believed fervently that by showing people the majesty of the Mayan civilization would lead to greater interest in (and greater funding for) excavation and research projects. Unrest in Mexico led to his ambitious project being delayed until the early 1920’s, when he would lead a team of professional archaeologists, researchers and artists in a massive project to uncover the city. (The Hacienda Chichen – headquarters for Morley and many other researchers, and now a luxury hotel – has a great list on their website of all the noted archeologists who helped dig out Chichen Itza).

I’ll follow up with another post on Doctor Morley soon, where I’ll look at the Carnegie Institution’s ambitious project to rebuild Chichen Itza. Thanks for reading!

Recent Comments