Charles Lindbergh – or a fictional version of him – is a major character in Flying Conquistadors. He’s a fascinating individual who played a very large role in the development of aviation, and was instrumental in the early days of both Pan Am and Eastern Airlines. His legacy is, of course, complicated by his involvement with the America First Committee, which opposed U.S. involvement in what would become World War II. But those later years (I define “later” in this instance as post-1930), also marked by the tragic murder of Lindbergh’s son, are not the focus of this piece . . . or the book, for that matter.

Fame came to Lindbergh in an instant. When he landed The Spirit of Saint Louis at Le Bourget Airport in France on May 21, 1927, he instantly became the world’s most famous man. 150,000 people were waiting for him that night in Paris, dragging him out of the cockpit and carrying him over their heads. When Lindbergh returned to the U.S. (he and his plane rode back on the U.S. cruiser Memphis), some 4 million people witnessed his ticker-tape parade in New York City.

But Lindbergh wasn’t through flying the Spirit yet. To promote aviation – and in conjunction with the release of his autobiography, “We” – Lindbergh embarked on a Guggenheim-sponsored tour of across the United States, taking his famous monoplane to 82 cities in all 48 states. Huge crowds swarmed Lindbergh and the Spirit at every single stop.

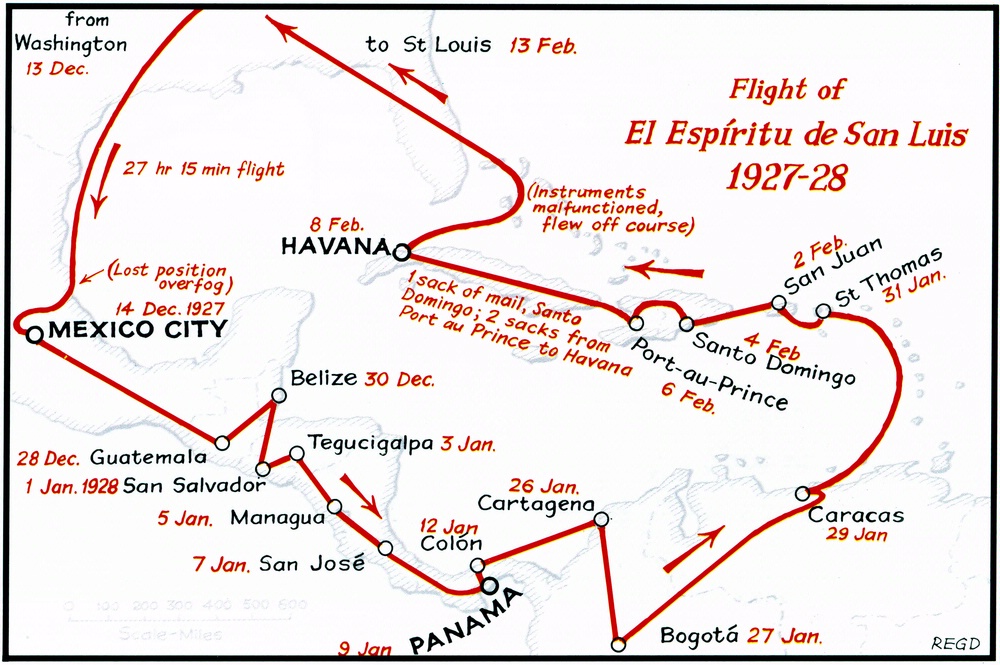

Lindbergh had first met Dwight Morrow, U.S. Ambassador to Mexico and the pilot’s future father-in-law, in Washington on his return from Paris. It was Ambassador Morrow who first suggested that Lindbergh do a second “Good Will Tour” to Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. On December 13, 1927, The Spirit of Saint Louis took off on its final grand tour, flying from Washington, D.C. to Mexico City.

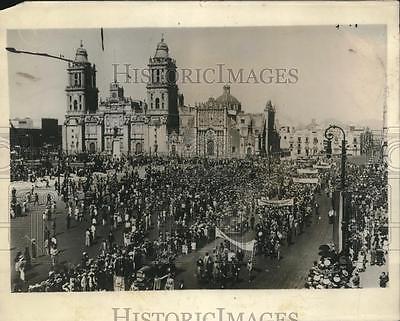

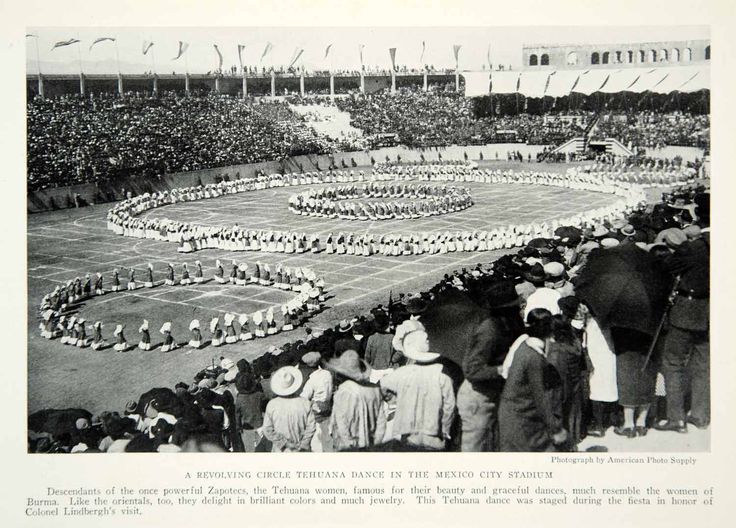

While he may have been expecting smaller crowds outside the U.S., the opposite was the case. Some 200,000 people witnessed his arrival in Mexico City, which was followed by a workers’ parade with 100,000 participants and hundreds of thousands more lining the parade route. In the days that followed Lindbergh would be the star attraction at a bullfight, more ceremonies, and countless tours with dignitaries.

(Historical note: it is during this visit to Mexico City that Lindbergh was first introduced to Ambassador Morrow’s daughter, Anne. As legend has it, she was not happy to see the famous flyer invade the tight Morrow family environment. Charles and Anne would marry a year and a half later.)

From Mexico City, Lindbergh then travelled to Guatemala where he received another rousing reception. He then flew the Spirit from Guatemala northeast toward Belize, flying over hundreds of miles over the dense jungle. It is during this flight Lindbergh reported seeing Mayan ruins from the air. Some reports say he spotted “a white city,” while others maintained he saw “an amazing ancient metropolis.” These reports sent archaeologists into a tizzy, trying to determine in Lindbergh had identified previously unknown Mayan sites. Those sightings of ruins by Lindbergh in the Spirit inspired parts of Flying Conquistadors.

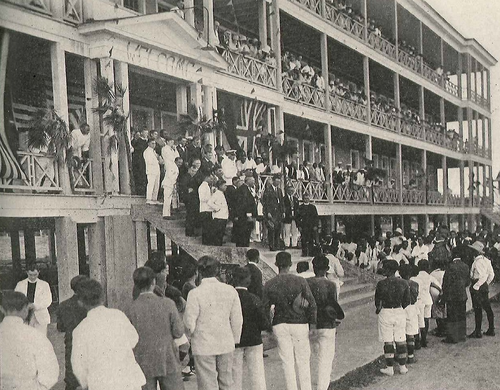

In Belize – which was the British Honduras at the time – Lindbergh was again treated like a king, and thousands turned out to hear him speak. The scene would be repeated time and time again, as Lindbergh then flew the Spirit south over Central America. After visiting Bogota and Caracas in the final days of his epic 1927, Lindbergh flew to St. Thomas and then across the Caribbean to Havana.

There is an interesting story about Lindbergh’s departure from Havana, a story that might have had a very unhappy ending. Keep in mind the Spirit had no radio and it was the middle of the night. Here’s Lindbergh in his own words from a later autobiography:

Over the Straits of Florida my magnetic compass rotated without stopping…. I had no notion whether I was flying north, south, east, or west. A few stars directly overhead were dimly visible through haze, but they formed no constellation I could recognize. I started climbing toward the clear sky that had to exist somewhere above me. If I could see Polaris, that northern point of light, I could navigate by it with reasonable accuracy. But haze thickened as my altitude increased….

Nothing on my map of Florida corresponded with the earth’s features I had seen…where could I be? I unfolded my hydrographic chart [a topographic map of water with coastlines, reefs, wrecks and other structures]…. I had flown at almost a right angle to my proper heading and it…put me close to three hundred miles off route!

The gods of aviation looked favorably on Lindbergh that day, and he was eventually able to find Florida and made his way back to St. Louis. A few months later, The Spirit of Saint Louis would make its final flight, with Lindbergh piloting it to Washington where it would become a star attraction for the Smithsonian.

Recent Comments